The following tutorial is a relatively quick and simple how-to for photographing 2-D artwork such as paintings, textiles, glass-covered images, reproducing newsprint, and more. I will also cover how to correct and post process the photographed artwork.

I have found the easiest and most controllable way to photograph artwork is to use strobes or off-camera flash. If you are unfamiliar with off-camera lighting in general, I highly recommend you spend (a lot) of time reading and exploring www.strobist.com.

Let's go over some basic gear needed to shoot artwork:

A good lens, with no distortion or vignetting (see lens reviews at Photozone). Macro lenses are an obvious choice. Strobes or off-camera flashes, preferable with a PC-Synch port. Flash transmitters or receivers such as optical slaves, Cactus V2s, Pocket Wizards, or Nikon's CLS system. You can also use flash cords. Light stands that can go to the full height of the work you are photographing. Tripod to keep your camera steady, and to help keep the camera square to the artwork. Grey card (not essential, but will simplify the entire process). Camera! (Digital is preferred, so you can preview your work.)

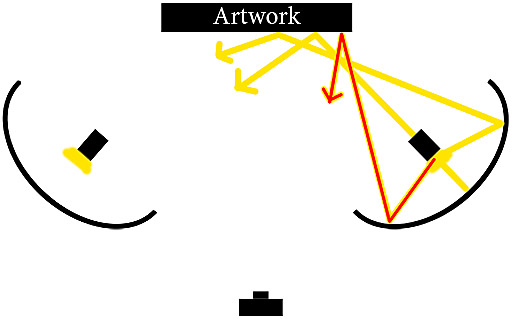

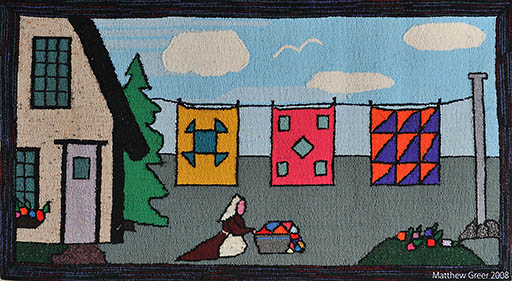

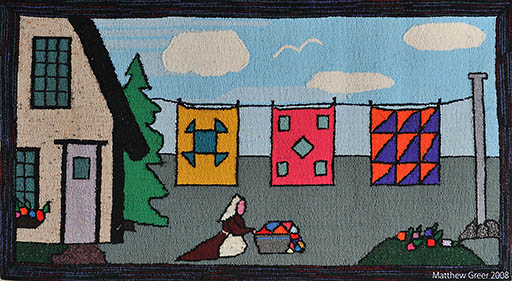

For photographing wall-hung artwork, I have found that using two flashes, each on a lightstand and each reflected into an umbrella, the best setup. One light goes on each side of the artwork, at the same height as the artwork and at 45° to the artwork. Below is a setup image of a hooked rug I photographed recently. I've increased the contrast so you can more easily see how the light is falling on the art.

As you can see, the light is falling evenly on the hooked rug in the image as the overlapping fading lights balance out. Closer to the lights, however, the light falling on the wall is too strong, and if the artwork was within that range, it would result in bright spots at the edges.

How to set up your lights and your camera:

Set your camera's ISO to its lowest native setting (this will ensure optimal image quality). Set your camera's highest synchable shutter speed (you'll want to eliminate as much ambient light as possible). Set your camera's white balance manually (see paragraph below), or to cloudy, as that generally creates pleasing colours with flash. Set your aperture to between f/5.6 and f/11 - you'll want good depth of field and sharpness, but have some flexibility for controlling the light getting to the sensor. Set all your flash triggers so they are all on the same channel. Start with your flashes at 1/2 power. Do some test shots, watch your camera's LCD and histogram, and vary your flash power and aperture to get the light level right. Try not to bring your flash power up to full (1/1) power, as this will eat through batteries faster, and cause slower recycling times. Point your flashes into their respective umbrellas, and then the umbrellas at 45° angles toward the artwork. Start with the lights approximately 1 metre (3.23 feet) out from the wall, and 1 metre to each side of the artwork. Shift them around as needed.

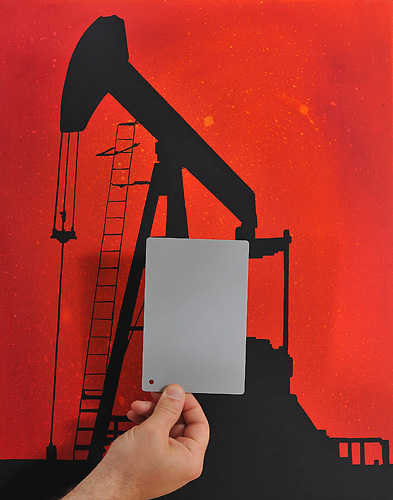

Once the lighting has been set up, the next step (not entirely necessary, but this will make post processing far easier) is to take a white balance reading from a grey card. The easiest way is to take a manual white balance reading with your camera (check your manual for specific directions) while using the same lighting setup you'll use for photographing. Your other option is to shoot RAW, just photograph a grey card under the light being used, and use the grey card to set the white balance in post processing, with a program like Adobe Camera Raw (ACR). I personally find the first to be much easier.

Of the above-mentioned forms of artwork, I've found paintings to be the most difficult - oil on canvas in particular. That is because the reflective properties of the oil paint combined with the minute 3-D texture of the canvas make eliminating reflections very difficult. There is much you can do in post processing to tone down or eliminate these mini reflections or bright spots, but if you can get the shot right at the outset, your processes will be much faster and easier.

The image below is of a painting by Edmonton, Alberta painter Melissa Ryan that I photographed (for reproduction purposes) last week.

This particular piece was difficult because of the size (over a metre [3.28 feet] wide). While I was comfortable with small amounts of glare on the painting (small amounts would be just enough to show the texture of the canvas and the oil paint, but excessive glare would destroy detail and change the brightness of the painting to something the painter had not intended), my initial shots showed too much glare, especially near the edges. Below is an example of the initial poor shot (left), and the shot with the corrected lighting (right).

Much of getting lighting correct is trial-and-error (always double check your images on your camera's LCD), but there are some general rules that can be followed to avoid or easily correct your mistakes.

In the initial setup shot, the lights were at 45° angles to the artwork. Theoretically, this should mean that the light would leave the artwork also at 45°. The issue is that when reflecting light into an umbrella, the light ends up striking the subject at multiple angles. In this case, that's everything from about 10° to about 80°. This means that some light ends up reflecting straight back into the camera lens, showing up as a reflection on the painting.

As you can see in the sketch above, the stream of light drawn in red is streaming back toward the camera, and would show up as a bright reflection. To remedy this issue (if it occurs), reduce the angle between the light source and the wall (move the flash and umbrella closer to the wall) and keep the light source pointing straight at the artwork.

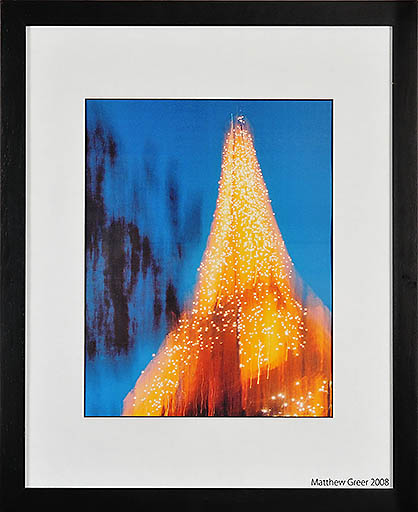

Textiles and glassed-in images follow the same rules, but I've found them to be easier to photograph than oil paintings. With glassed-in images, you'll really want to make sure your shutter speed is as high as possible, as this will help eliminate any background reflections on the glass (including your own reflection). With this said, radio triggers are best for glassed-in work (such as Pocket Wizards or Cactus V2s), because you won't be using your on-camera flash to trigger the strobes, so there will be no light source on your camera that can reflect in the glass.

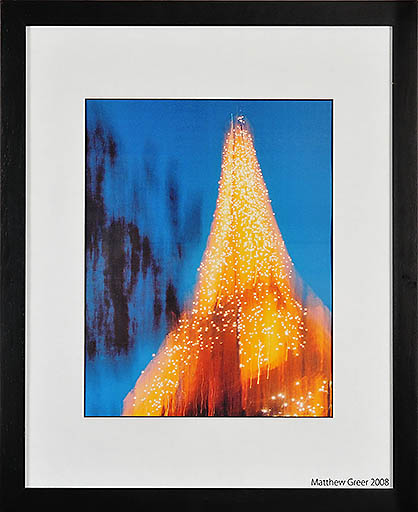

This is a glassed-in photograph of the Eiffel Tower. Note that there is no glare or reflection in the glass.

This is a hooked rug, hooked with cotton and wool fibres. Glare and reflection aren't a significant issue with these materials, but even lighting is essential.

This is a glassed-in photograph of the Eiffel Tower. Note that there is no glare or reflection in the glass.

This is a hooked rug, hooked with cotton and wool fibres. Glare and reflection aren't a significant issue with these materials, but even lighting is essential.

Photographing Newsprint and Other Small Artwork

For newsprint and other small, 2-dimensional artwork, a one-flash, one-umbrella setup works quickly and easily. Below is the setup, and shooting can easily be done with the artwork flat on the floor and shooting straight down on it.

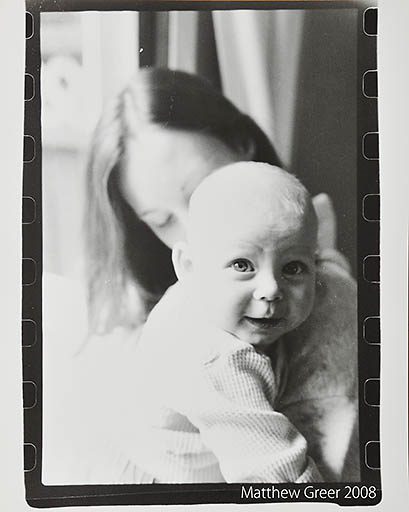

As you can see, the light is very close to the artwork (in this case, a black and white 8x10 print on matte paper). There is just enough space for me to shoot down on the work without the umbrella getting in the way of the shot. There is no reflection and the light is even. Below is the resulting image.

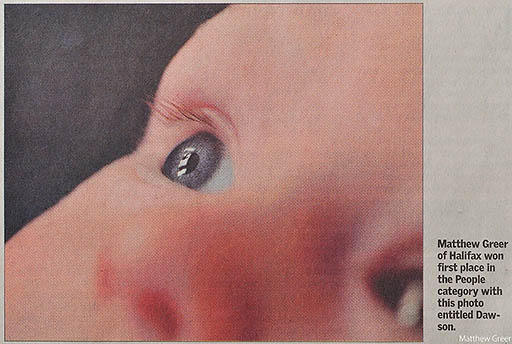

And now below, is an image of a newspaper printed photo (of an image that I won a newspaper-based photo contest with).

Post Processing Artwork

Finally, we'll cover post processing artwork. There are a number of issues that have to be considered when professionally photographing artwork. First of all is perspective. When shooting artwork, every effort should be made to photograph the image perfectly square. It is not always possible to get it perfect, and with Photoshop, it is quite easy to correct perspective. I have already written an article on correcting perspective, covered here.

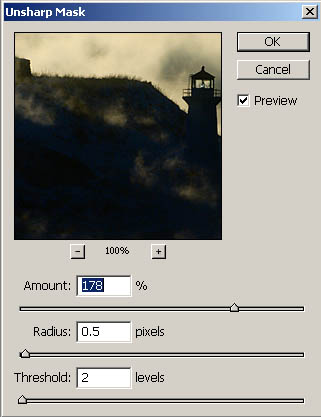

Another aspect you'll want to control is sharpening. Again, I've covered that in a previous article, here.

Finally, an issue we discussed earlier in the article is even lighting across the image. Every effort should be made to get this perfect while shooting, but not all lighting variations can be seen on a camera's LCD. If, after shooting artwork, you find that one side or corner of an image is lighter than it should be, it can be easily corrected in Photoshop.

With the image open in Photoshop, create a new layer (Layer > New > Layer... or Shift+Ctrl+N). Change the Layer Blending Options (drop-down menu in the layers tab, Window > Layers or F7) to Soft Light. Select the Brush Tool (B), choose a brush size that will be approximately half of the area you want to darken (use the [ and ] keys), and soften the brush edge all the way (use the Shift+[ keys). Set the brush opacity to around 15% (simply pressing 1 + 5 on the top row of the keyboard will do this). A lower opacity and you won't see much change; a higher opacity and it will be difficult to blend the brightnesses together. Paint the lighter area, one stroke at a time. If you need the area darker, click and paint again. If you need it lighter, Ctrl+Z to undo the change, reduce the opacity, and paint again.

If you have any questions or comments about this post, please Email me.

Finally, a thanks to Melissa Ryan and her beautiful paintings, and Brian Larter for getting us in touch with each other.

Matt